The idea of the fork() system call is very beautifully described in the paper “The UNIX Time-Sharing System” by Dennis Ritchie himself and Ken Thompson during their days at Bell Laboratories.

UNIX, as we all know is one of the most widely used operating systems. The present day MacOS and Linux are both based on UNIX. The versatility of both these platforms is due to the clear thought process that went in to designing UNIX.

I hate reading technical papers, because half the time, to be honest, I can’t understand what they are talking about. But if you read the paper linked above, which by the way is a very easy read, you will learn a lot and the best part, it’s all from the horse’s mouth.

Why fork()?

To answer this question, first let’s look at what happens when you try to execute a command from the command prompt in bash. For example,

$ ls -a

The shell checks to see if the first word after the prompt “$” is a built in shell command. If not, it assumes it is the name of a binary. The next piece of information “-a” in this case is passed in as a command line argument to the executable. In this case, we are interested in seeing all the files present in the current working directory.

When you hit enter, the shell knows you are done typing, and will load the respective executable file from the disk to the main memory, if the name of the executable is valid that is. Once the program is loaded to main memory, the system will start executing all the machine instructions starting from the main function of the executable.

When a program such as “ls” starts running, it has no idea about the other programs already being run by the operating system. As far as it is concerned, it is the only “process” running on the system and thus it has exclusive access to memory, hardware and other resources like the cache, storage, etc. This abstraction of a “process” is achieved with the help of time sharing or in more technical terms, context switching. The “context” for any given running program is maintained by the operating system which is information about the program counter, the stack frame, main memory, open file descriptors, etc.

So what happens to the shell when you press enter?

The shell is still there. It hasn’t gone away. If it did you would be in deep trouble! So when you hit enter, the shell does something important, it asks the operating system to create a clone of itself. At this point we have two shells running, one, the parent and the other, the child, with a copy of the parents “context”.

A copy?

Well, not really. The copy is an illusion too! The system uses a “a copy on write” mechanism. What it means is that for the most part, the child shares the context of the parent. If at any point the child tries to change this context, the system would then initiate a true copy to keep the parents state clean from corruption.

Coming back to our previous point, once the clone has been made, the child will ask the operating system to execute the provided command in its context. Even though what you see on your screen is in the context of the parent’s process, you may still see some output from the child process. This is because as mentioned above, the child process inherits the parent’s file descriptors. So “cin“, “cout” and “cerr” also known as stdin, stdout and stderr (not entirely true, but let’s just assume so) are shared. If there were any more file descriptors, those would be shared too.

Once the child finishes executing, the parent process is notified and the parent, in our case the shell, will resume its normal operation. But, before resuming, the parent must must do some cleanup. The way UNIX works is that after the child finishes execution, UNIX keeps it in a terminated state with its memory map still in tact, hence a ZOMBIE, and thus, the parent must clear this memory map by REAPING the zombie.

Q. How does the shell create a clone?

pid_t fork(void);

Q. How does the child ask the system to execute the given program?

int execve(const char *path, char *const argv[], char *const envp[]);

Q. How does the parent reap the zombie?

pid_t waitpid(pid_t pid, int *status, int options);

Show me the code!

Okay, okay, here we go. In the first example below, we will see how to fork a process and do some analysis.

#include <iostream>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <unistd.h>

int main() {

fork();

while(true);

}

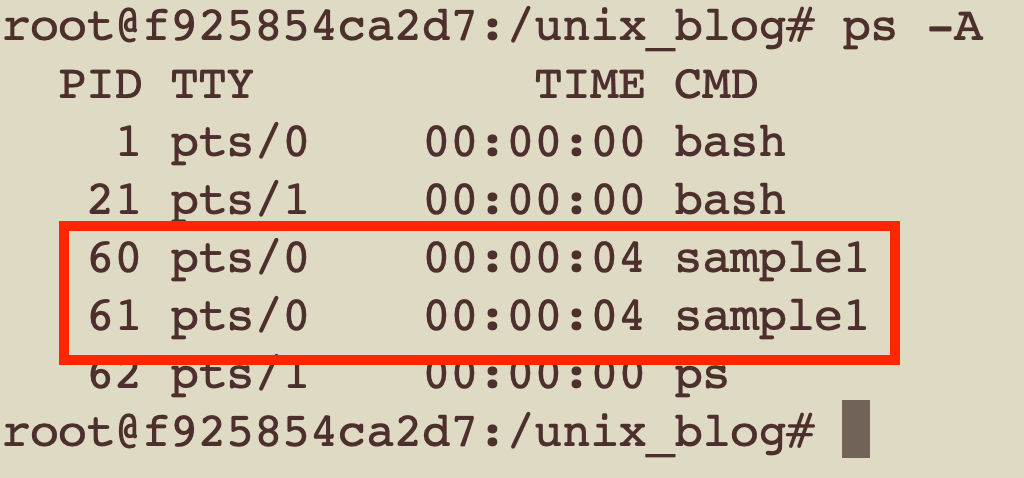

In the above code, we make a call to fork() and spin an infinite loop. Once you run the code, you should see two instances of your process as shown below.

The code below shows you how to differentiate between the parent and the child.

#include <iostream>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <unistd.h>

using namespace std;

int main() {

pid_t pid = fork();

if(pid == 0) {

cout << "Hello, I am the child process with pid = " << pid << endl;

}

else {

cout << "Hello, I am the parent. My child is pid = " << pid << endl;

}

while(true);

}

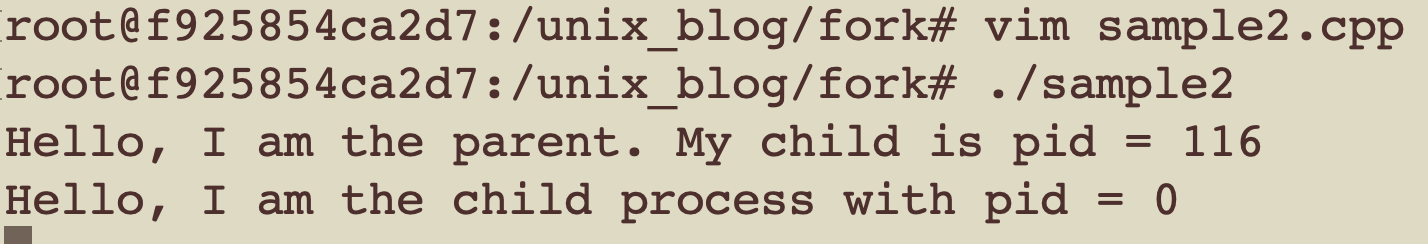

In the above code, the parent process receives the pid of the child, the child receives a pid of 0. But there could also be an error, in which case -1 is returned to the parent and no child is created.

After executing the above code, you will see the output of the two processes print to the same terminal window. This is because when you fork a process, the child process will inherit all the open file descriptors from the parent. The parent already has an open file descriptor to stdout and hence the child’s output is printed to the same descriptor as well as shown below.

Now let’s look at some code for cleaning up. As we discussed above, all parents must clean up after forking and the way to do so it use the waitpid() function. By default the options parameters is 0. This tells waitpid that it must pause the execution of the calling process until the child (passed in pid parameter) finishes execution.

The signature of the waipid() function is as shown.

pid_t waitpid(pid_t pid, int *wstatus, int options);

Let’s look at some code.

#include <iostream>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/wait.h>

#include <unistd.h>

using namespace std;

int main() {

pid_t pid = fork();

if(pid == 0) {

cout << "Child: Hello, I am the child process with pid = " << pid << endl;

cout << "Child: I am about to start some long task." << endl;

sleep(10);

cout << "Child: I am done executing the long task" << endl;

}

else {

cout << "Parent: Hello, I am the parent. My child is pid = " << pid << endl;

cout << "Parent: I am going to wait for my child to finish execution" << endl;

int status;

pid_t child_pid = waitpid(pid, &status, 0);

cout << "Parent: Child " << child_pid << " finished execution hence I am done." << endl;

}

}

The code above is fine if we have just one child. But what about having multiple children. So how do we setup waitpid() for this situation? Let’s take a look at the code example below.

#include <iostream>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/wait.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#define N 2

using namespace std;

void longTask()

{

pid_t pid = getpid();

cout << "Child(" << pid << "): Hello, I am the child." << endl;

cout << "Child(" << pid << "): I am about to start some long task." << endl;

sleep(10);

cout << "Child(" << pid <<"): I am done executing the long task" << endl;

exit(0);

}

int main()

{

pid_t children[N];

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++)

{

pid_t pid;

if ((pid = fork()) == 0)

{ //Child

longTask();

} else {

children[i] = pid;

}

}

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++)

{

cout << "Parent: Hello, I am the parent. My child at " << i << " is pid = " << children[i] << endl;

}

cout << "Parent: I am going to wait for my children to finish execution" << endl;

int status;

pid_t child_pid;

while ((child_pid = waitpid(-1, &status, 0)) > 0)

{

cout << "Parent: Child " << child_pid << " finished execution." << endl;

}

cout << "Parent: All my children finished execution." << endl;

}

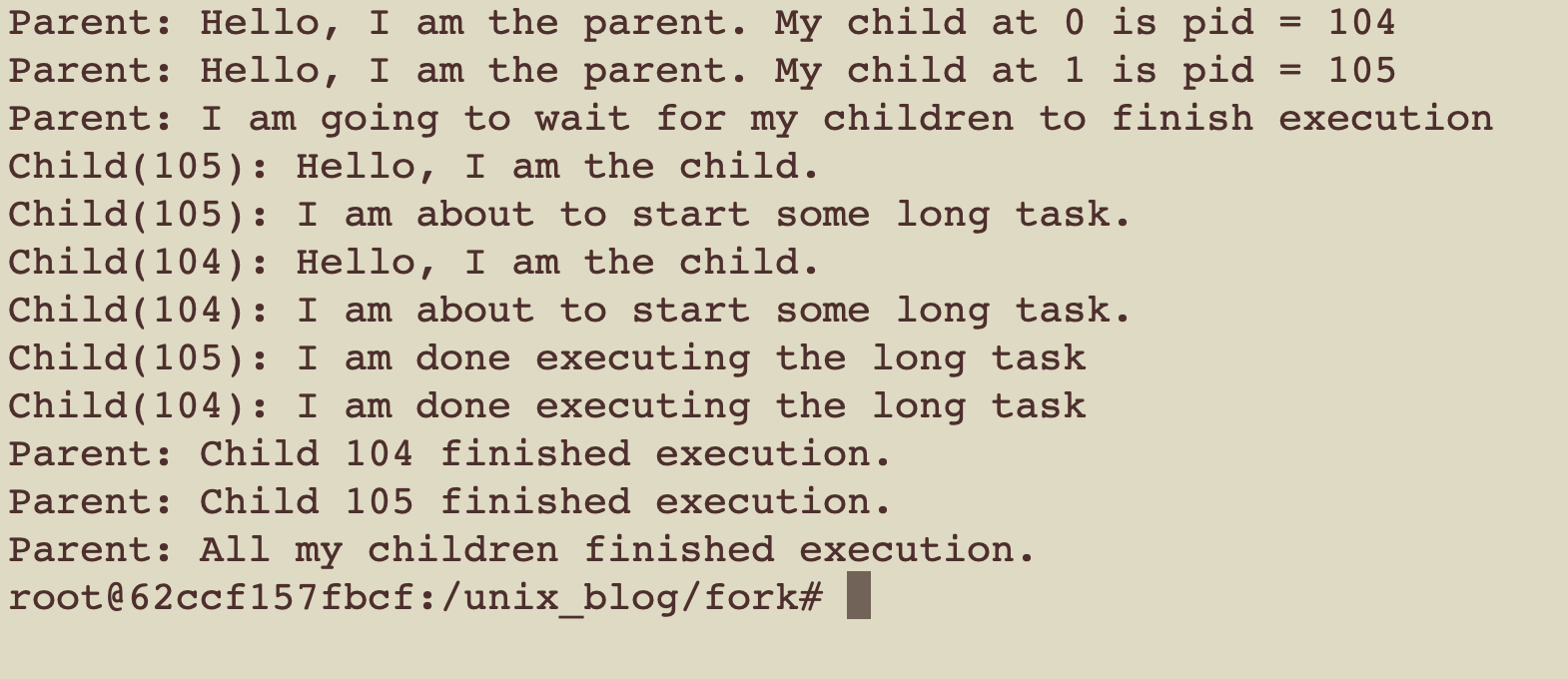

In the above example, the parent is creating two children in the for loop. Each of these children are going to execute some long running task. Mean while, the parent will wait for these children to finish by passing in -1 to waitpid() which tells waitpid() to wait for all children. Since there are multiple children, this call to waitpid() is in a while loop. As long as there are children to reap, the condition will be true. Once all the children have been reaped, the call will return -1 making the condition false and that’s how the parent knows that all children have finished.

The image below demonstrates that you can never rely on the order of execution of the processes. However, there is a way to wait for processes in the order they were created. I leave that to you to investigate.

The usage of the term finished above is not necessarily correct. There could be many situations for a process to terminate. It could’ve run successfully, it received a signal that it did not handle, or if the child has stopped. This information can be retrieved through the status pointer that was passed in to waitpid(). There are several macros available to make sense of this information. These are defined in wait.h and to check if the child terminated gracefully, you can use WIFEXITED(status).

Thus far, we have seen how we can use the fork system call to duplicate our process and we know that the shell uses the fork system call to duplicate it self by spawning a child process, but what does the child process do? Well, the child process will call the execve() function passing it the name of the shell command or program we want to execute along with any arguments that we want to pass in. The execve() function replaces the memory layout of the child process and realigns the memory to the required layout of the program we are interested in.

The signature of the execve() function is as shown:

int execve(const char* path, char * const argv[], char* const envp[])

The method expects 3 arguments, the path to the executable, the list of parameters that need to be passed in to the program, for example “-l” to the “ls” command and any environment variables that need to be set for the program to run successfully. Both these arrays are to be NULL terminated and argv should have at least one value. It seems that it is a UNIX tradition to have the name of the program as the first value in the argv vector.

The return type of this function is int. But execve() will only return -1 in case of an error. Why? Well, if you think about it, if execve() is successful, the memory map of the calling process has been wiped out so execve() has no process to return to.

So let’s build a program that it self accepts command line arguments which for this article will be the program we are interested in running and a command line parameter that we will pass to it.

#include <iostream>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/wait.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <sstream>

#include <string>

using namespace std;

int main(int argc, char *const argv[], char *const envp[])

{

if (argc < 2)

{

cout << "Please enter a command to execute with an optional parameter" << endl;

cout << "For example: " << endl;

cout << "ls" << endl;

cout << "OR" << endl;

cout << "ls -l" << endl;

exit(1);

}

//Get all the environment paths in the PATH variable

char *environmentPaths = getenv("PATH");

char *const command = argv[1];

char *const parameter = (argv[2] != NULL) ? argv[2] : NULL;

pid_t pid;

if ((pid = fork()) == 0)

{

//Child

//Ensuring args is always NULL terminated.

//Doesn't matter even if parameter = NULL from above.

char *const args[3] = {command, parameter, NULL};

char *token;

token = strtok(environmentPaths, ":");

//Iterate through all the paths in the PATH variable.

//Append the entered command to each path

//and see if the executable exists at that path.

while (token != NULL)

{

stringstream ss;

ss << token << "/" << command;

string fullyQualifiedPath = ss.str();

execve(fullyQualifiedPath.c_str(), args, envp);

token = strtok(NULL, ":");

}

//If you reached here, the command was not found

//at any of the sub paths in the PATH variable.

//Perhaps the user wants to execute a binary

//in the current folder?

if (strncmp("./", command, 2) == 0)

{

execve(command, args, envp);

}

//If none of the execve above have executed,

//that means the binary has not been found anywhere!

cout << "Error: " << command << " not found." << endl;

exit(1);

}

else

{

int status;

waitpid(pid, &status, 0);

if (WEXITSTATUS(status) == 0)

{

cout << "Child terminated successfully" << endl;

}

else

{

cout << "Child did not terminate successfully" << endl;

}

}

}

The above code is very detailed and takes in to account traversing through all the paths in the PATH variable and even checking if the user is trying to execute something in the current directory. If we can’t find the executable, we print an error message.

Next Steps

There’s a lot that can be done with this program that is not demonstrated here. I leave it to you to try to implement some features of the shell like taking in multiple arguments instead of just one, piping the output to different commands and even redirecting stdout to a file.

All of this code is stored on my Github repository. Feel free to check it out and leave your comments down below.